Written in January 2021

Most materialists, even though they may have wanted to do away with all spiritual entities, ended up positing an order of things whose hierarchical relations mark it specifically as idealist.

Georges Bataille, Materialism

This piece returns to the fragments of an experimental auto-ethnographic journal that I kept during the early days of COVID.

It incorporates those entries into several thematic explorations and culminates with some discrete reflections on how my thinking and the key foci of my project have been reshaped in response. Most notable among these is a re-orientation from thinking about plant-human relationships to thinking about the historical return and correlate renegotiation of human, biological, and theological systems as it has been provoked by the pandemic.

In early March, our spring semester suddenly and rapidly segued into a dream. Later a semblance of conventional time would emerge groggy, ensconced in an ambient sluggishness that would come to pervade all the corners of our lives. My last in-person visit to our seminar took place in those very first moments of what would later become identifiable as an after.

Our new plague time was, back then, still like a delicate newborn, not because it was accompanied by the personal insecurities and existential determination of parenthood but because of the uncertainty inherent to suddenly sharing space with a new and alien presence.

I remember carefully choosing my position in the room that final night, trying not to touch my face. I recall my silent but petulant fury that another student had arrived sick, wrapped in a blanket with a cup of tea on the table in front of her. I can still channel the professor’s taciturn affect, hear his sober prediction that the day’s news out of Washington state was a sentinel of things to come.

How early in the story we still were.

The plague seemed to begin with a series of geographic signifiers; a relational map of markers and place-emblems associated with the alien visitor, threatening to bend space into strange Euclidean warpings (Braun 2008). At first, this new map felt cautionary, betraying alarm and a desire for containment.

Perhaps to the virus, we hoped to imagine, we were still inhabiting knowledge threshold zones, as if we might remain cartographic Renaissance sea monsters, undiscovered.

But, of course, we did not.

In coming weeks, the markers changed frequently as the plague story unfolded rapidly through a shifting series of collective attentional investments in remote places. Now, the map has been fully populated.

Today, Wu-Han no longer signifies a tragic apex and Washington state is no longer associated with shocking contagion or mortality. Louisiana has enjoyed its own period of emblematic meaning, but this too has passed.

Our geographic view has stabilized into a more conventionally imperial one. Many of us still look at geographic data aggregators often, following the plague’s ebb and flow across space, but the spread of the plague has a kind of innately distributed quality and our manner of viewing space like this has largely returned to normal.

Of course, the spaces of my own life seemed to change immediately too. The abject uncertainty of future time grew real in a way that was entirely unfamiliar, as if previously well-contained theoretical fascinations were now vivified. The possibility of funding for travel and field work seemed increasingly remote and my motivation for academic investment based on the already tenuous promise of career, grew increasingly quixotic. As the hope of containment dissolved, I grew increasingly attentive to my domestic confines.

More and more, I entered into and explored a kind of deeper intimacy with my plants. Every day it intensified until it felt more clearly like a practice. Paradoxically, in that regard, I don’t think I ever became so fully engaged with the problem of plant/human relationships at the heart of my research as I did in those first weeks and months. Almost immediately after the virus arrived, as if intuitively, I found myself turning ever further towards them.

As I write, the metaphor strikes me immediately - turning towards, as plants themselves turn towards the sun. And, just as swiftly, a second metaphor from some Cthulhic associational depth, disguised within an aphorism: under the sun, nothing ever changes. In the word play of my mind and with all that free time, I also could not fail to notice in my concurrent and increasingly focused care for plants that I was now focused instead on stores of the sun’s energy.

In the early plague’s act of stripping bare daily life, it was as if I had stumbled into Bataille’s solar economy, “the unilateral gift that the sun makes of its energy: a cosmogony of expenditure” (Baudrillard 1991). It was as if I was experiencing something ancient and true about the universe.

Like others, I suspect, it had been quite comfortably exhilarating to cast myself in the melodrama of the Anthropocene in recent years. For a peak moment, that pedagogical taboo with which we inculcate undergraduates learning to study the social world – that they must avoid claiming “now, more than ever” – was obliterated.

Instead we all indulged such license for presentism.

Now in the bright hangover light of the plague, such indulgence felt like a party trick or a maudlin toast - “tonight is special.”

Who among us was not special, to live in the Anthropocene?

Now, our new special cataclysmic plague moment was entirely unwelcome.

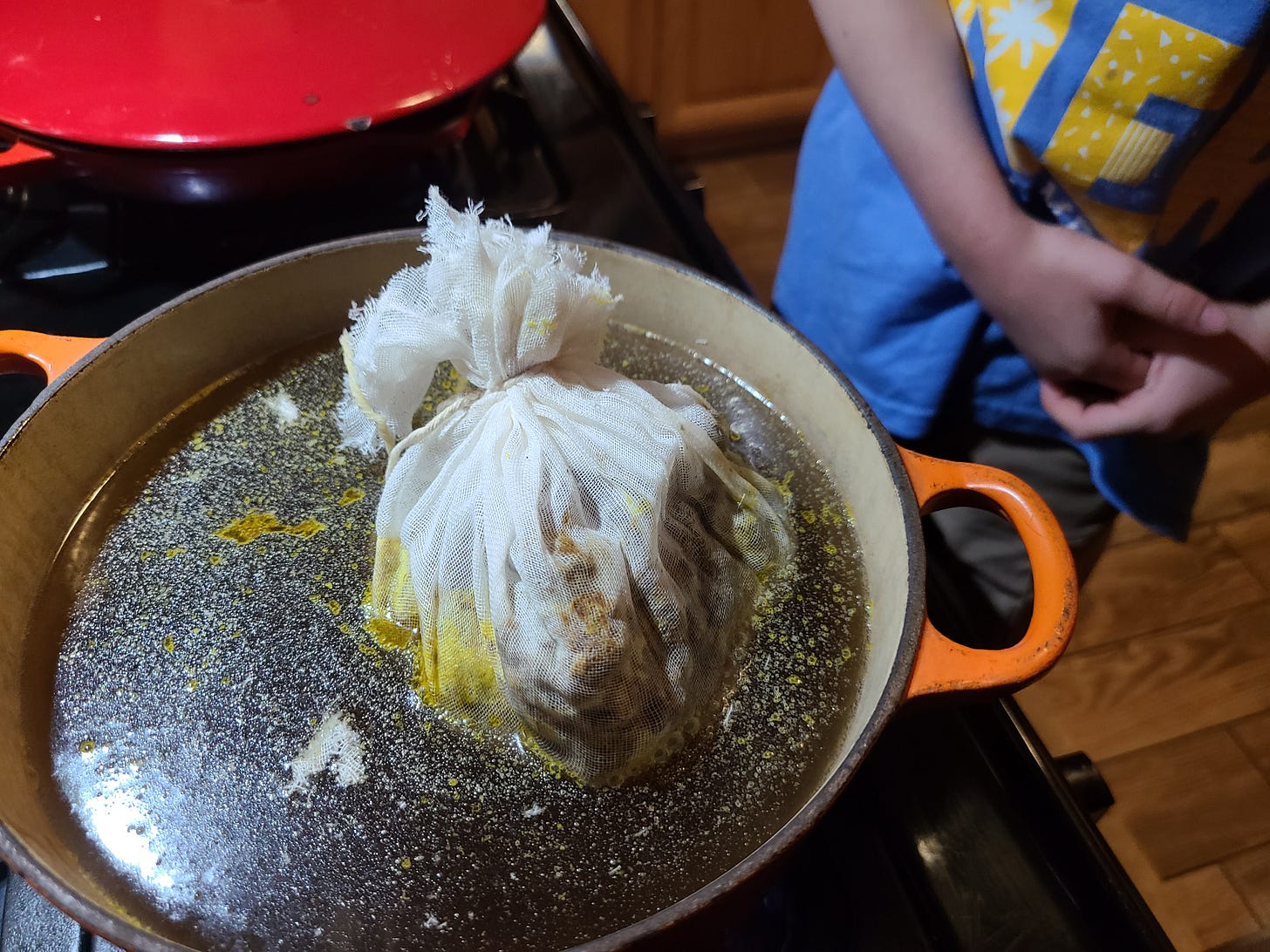

At this peak of our reduced social mobility, it was not futurity but traditionalism – a clamoring backwards - that seemed to emerge everywhere almost spontaneously, and assert itself desperately. Everyone seemed to make sourdough. Copious think-pieces confirmed this. We did too and in my home we also begun to ferment vegetables constantly. In both cases, the act itself was as if a plea – appropriating from Rilke, “who, if I cried out, would hear me among the [microbes] hierarchies?” We did not kneel, and we made no recitation. Yet we might as well have, preparing a sacrament in the form of a sugary medium or some shredded vegetables, like a ritual imploring these other microbes that they stay among us.

Granted, when we carefully placed our delivered cabbage heads in the shed, it was born of a diligent wariness towards ominous fomites, rather than storage for the winter, and they stayed there for only a few days. Yet all of it was oddly familiar, as if remembered from children’s books about frontier life or some kind of epigenetic intergenerational memory transmission.

In truth, most of the actual changes to how I lived were small. Indeed, if I bracket off the sudden disappearance of socialization, I am left with something simple and almost unremarkable – I simply didn’t go to stores much anymore. Of course, I qualify this to account for our vastly intensified reliance on Amazon and mobile-integrated neo-feudal delivery services, yet, it’s true.

The contours of my daily life were most notably altered in my avoidance of stores as well as the creeping shock of recognition of just how frequently I had gotten used to doing so, which followed.

As well, in those early months, I was mired in the shame of not working effectively and of wasting time. I should be productive, I knew. I was always aware that I was not doing what I was supposed to be doing. It was like a shame accelerator and blew forth like wind as I imagined that somehow I should be able to open that time up like a gift; that if I were a better person, I could receive it as a plane of immanent possibility. That I might invent the secret routine of a “highly effective person” or become an avant-monastic. But there was a problem with this line of thought.

When I thought of the monk in his temple, who rises before the sun preparing to contemplate god and being – the practicing metaphysician par excellence – I notice a critical difference. He finds himself on a reliable plane of stillness. And this timelessness of the monk’s god, the object of his contemplation, is anathema to the impressive mutability and scope of the alien virus.

Of course, I am hardly naïve that this blaming of myself, as with the frequency of my store visits and consumption, must be a structural imperative of neoliberalism.

And while the virus had shaken up its strictures, at other times it seemed to embody its core ethos, profoundly cool in its innovation and endlessly hip in its sweeping territoriality.

It seemed forever adaptable, ever-changing, so far ahead of the curve that we simply couldn’t keep up. I learned to trust only that, above all else, whatever it did next would be spectacular and impressive. In this regard, the virus actualized capitalism better than David Harvey at his most scathing ever could.

So I simply grew my plants in quiet but patient shame, left with little else. At least I had the sun. In tweets and fragments of others' thoughts, I recognized a common experience – of days that drag but never end yet end all too suddenly.

A few weeks into quarantine, I began germinating one hundred Desmodium gyrans - Telegraph plants, which are famous as one of only a handful of plant species that are capable of rapid movement visible to the naked eye. In doing so, I was rekindling my own long obsession with a particular plant that had obsessed Charles Darwin too. One of his final books, The Power of Movement in Plants (1880), compiled the results of several years of working with this same species to understand phototropism.

My own empiricism was more irrational. Once upon a time in 2014, I had wanted to make a time-lapse art video of the rapid-moving plant but found them nigh impossible to cultivate. Yet I continued trying and it was only persistence, not knowledge, which began to shape the goal of their successful cultivation into my white whale.

This is an admittedly slippery metaphor, besot with many interpretations, but there is a common reading in which Ahab’s terminal desire serves as the crescendo of a leitmotif about capitalism, extraction, the industrialization of nature and colonialist possession. Likely, I can at least partly trace my own obsession to that reading, or the metaphor would not arise at all. Surely, in some small and colonialist-haunted way, I want to master them or extract something from them. Surely there is also, here, a compulsive aspect to my obsession which explains why it returned at this time.

It is true that telegraph plants contain a minute quantity of tryptamine alkaloids and that similar plants which contain larger amounts thereof are often cultivated by armchair psychedelic chemists as a means to produce them. Yet this was neither compelling nor practical for me. I have no interest in extracting from them, only in growing them to watch them move, in their difference from me. Further, as I now find myself living in Louisiana, it would be a catastrophically bad idea.

Among our other provincialisms, we also boast a unique state law which strongly forbids cultivation of nearly all uncommon psychoactive plants that are freely cultivable in other U.S. states. Ironically, I had thrown caution to the wind and grown a coca plant around Christmas time when someone sent me seeds unexpectedly. I simply couldn’t fathom punishment, much less botanical identification recognition by any law enforcement officer. I’ve never ingested cocaine in my life and when the plant died, no obsession to try again followed.

Yet here I found myself all over again, tending as best I could, to these dancing plants. I have lost count by now of how many times I have tried to cultivate this plant. I can only say that I began in Los Angeles in 2014, that I repeated my efforts in England and again in Maryland and that none of them before now had survived for long.

This spring, I transported them across town in the trunk of my hatchback, photographed them repeatedly, sunburned them, attempted to remove mildew from them with a baking soda solution that nearly killed them, desperately flushed them with water, and discovered their predilection for a bit more acid in their soil. I sought advice online repeatedly, so thoroughly that I even came across my own posts from 2016, deep within pages of Google Search results.

At one point, I started a long poetic post online (though I could never find the vim to complete it) about the existential angst of botanical cultivation, how it’s not for the faint of heart. I was thinking of all these alien miseries and the perplexity of my poor calculations, how I seemed to keep choosing the wrong option from the conflicting advice of strangers.

For a time, I kept a journal which includes the following undated entry from late Spring, “today I am weary and forlorn / my plants are unhappy / the weather outside boasts unseasonably dry air.”

At another point, I considered making a kind of short art publication about people’s relationships with their plants. It began from the small insight that there is something taboo about relating to plants at all, which made these person/plant dalliances necessarily secretive.

It occurred to me to compare this to a kind of quotidian multi-species infidelity.

And yet after all this labor and my near complete failure, it was undeniable that even this most vibrant among plants resisted my efforts at care. I found myself asking what the nature of this care really was. Slowly, I came to recognize that for all that plant being is real, it will remain alien to me. It will not be coaxed into an academic paper. I do not enter a love affair for knowledge, but aesthetic experience. Thus, during the plague, I finally abandoned my notion to study the person/plant affairs. I realized, finally, that I was interested in plant time as some kind of analogue for another form of human time.

Ironically one of the last texts I had selected to present in our seminar, by Natasha Myers, is about ecological prefiguration at the end of the world and the possibility of gardens as the site of new stagings for a futurist nature/culture. Less than a year ago, I could still find an adrenal charge in such notions of apocalypse. Now I could not help but wonder about an almost theistic undertone unmasked: with the plague, and in the presence of alien life/not-life (a new and almost categorical unknown, it seemed at first); in turning again and again towards my plants, I sometimes felt as if was I worshipping the sun in the form of my plants - the first and primary mediator of a solar intimacy.

Perhaps such elemental undertones of my wandering mind are unsurprising, after so much saturation with the proliferation of a kind of thought in which the Anthropocene had felt both new and sexy. It had become easy to picture the link between the age of fire and the end of time; comfortable, even, to figure an agentive human thing that spanned time. To think the human like a god, if one is to be honest about it.

Now, some days, I confess, I think of the virus like a god too. Or perhaps simply an alien intelligence - a vast unknown that is always fluid and morphs ceaselessly. Lately in the news of freshly discovered mutations which threaten the efficacy of the vaccines, arriving just as the vaccines are being released to the public, the plague feels like a trickster and I forgive my mind for its irrational play beyond reason.

After all, here we are, with the plague, in a new epoch without neat precedent and the lived-daily question of what comes next. In this rupture, it seems apparent that our myths of progressive modernization have encoded a “flight into cyclicity” rather than a “break from the cycles of time” (Land 2014). It feels palpable with the virus beside us, that “futurity is unevenly distributed because it is scarce” (ibid). Because we will not all survive, there will be no “universal politics” of ecological cataclysm (Chaudhary 2020), whether it emanates from climate catastrophe or zoonotic pandemic.

Implicit in the experimental autoethnographic journal I have offered here is this one important proposition: with the undeniable absence of a universal politics irreconcilably now upon us, we are witnessing the beginning of a diversity of gestures to “hack” time. In such gestures, larger political terms are being reworked experimentally, in ways that are not explicit.

For instance, to interpret the proliferation of fermentation and bread starter as forms of offering (to microbes) is not simply word-play. It also resembles, I argue, something like a method of “hyperstition:”

a neologism that combines the words “hyper” and “superstition”, in order to describe the action of ideas that in the end turn into reality. While superstition is considered a mechanism to produce false ideas and groundless beliefs, hyperstition means a potent and mobilizing idea, carrying the ability of materialization into reality at some point in time (Borges 2014).

Borges’ invocation of hyperstition is part of a larger theory of technoshamanism (2017) which explores a largely secularized practice of “transversal shamanism” – a practice of engagement with alterity and communication with all forms of being – human and otherwise.

Hyperstition is a critical strategy for actualizing from the “community of specters,” a virtual realm of possible beings. I am arguing here that the virus has come upon us as if an alien life form, inaugurating the arrival of the unknown unknown (Cooper 2008) and forcing us to reorient the human within time in new ways.

Writing about the plague in Athens last year, during the early days of COVID, Fabián Ludueña Romandini (2020) discovered a foundational precedent to this moment, in the collapse of both human and divine authority as the populace was confronted with zoonoses:

The absolute depoliticization of the human world is succeeded then, by the absolute politicization of nature, which only speaks the language of death. In this sense, zoopolitics begins by order of non-human nature, the first foundation on which to measure the entire order of the community. The appropriation of the ungovernable and potentially deadly natural, is the first constitutive political act, and the zoopolitical gesture consists precisely in the construction in the realm of the world, of a habitable ecosystem for the human animal.

With the virus, then, we have experienced the sudden disappearance of this ecosystem and, as a result, a secondary rupture in the politics with which it emerged. With the virus, we are experiencing the return of a primary Euro/Western historical crisis, and a need to reject the Greek isonomia, an “affirmation of the homogeneity of space” (Stengers 2018) in favor of a new diplomacy between human and more-than-human actors which acknowledges the “partial articulations” (ibid) of their antagonistic realities.

As the virus reshapes us in our habitat, it then also forces us to revisit a ruptured political schema as old as antiquity and, in so doing, revivifies a constitutional renegotiation of biological, theological and political commitments.

References

Baudrillard, Jean (1991) When Bataille attacked the metaphysical principle of economy. Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory. 15(1-3): 135-138.

Borges, Fabiane M. (2017) “Ancestorfuturism: Free cosmogony — ‘d.i.y. rituals.’”

Borges, Fabiane M (2014) “Seminal thoughts for a possible technoshamanism.”

Braun, Bruce (2008) Thinking the city through SARS: Bodies, topologies, politics. In S. Harris Ali and Roger Keil, eds. Networked Disease: Emerging Infections in the Global City. London, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Chaudhary, Ajay Singh (2020) “We’re not in this together: There is no universal politics of climate change.” The Baffler 51.

Cooper, Melinda (2008) Life as Surplus: Biotechnology and Capitalism in the Neoliberal Era. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Land, Nick (2014) Templexity: Disordered Loops through Shanghai Time. Shanghai: Urbanatomy Electronic.

Myers, Natasha (2019) “From Edenic apocalypse to gardens against Eden: Plants and people in and after the Anthropocene.” In Kregg Herrington, ed. Infrastructure, Environment, and Life in the Anthropocene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Romandini, Fabián Ludueña (2020) “The plague and the end of times.” Wrong Wrong Magazine 18. Available from

Stenger, Isabelle. (2018) " The Challenge Of Ontological Politics." In Blaser, Mario and Marisol de la Cadena. A World of Many Worlds. Duke University Press.